After learning that Nice and Marseille are currently at the top of France’s Best Places to Live If You Want to Catch the Coronavirus, I felt an overwhelming urge to play cyber-hooky and do something different for a change. My mind wandered back to a comment I made in one of my reviews: “. . . I choose not to review films—my tastes in film are so radically different from the consensus that I would fear for my life.”

Hence the reason for posting this on Super Bowl Sunday, when my dominant demographic (Americans) is binging on booze, guacamole and TV commercials. I’m secretly hoping no one will read this. I’ve been working on this one for months, stuck in an endless Hamlet moment . . . “To post or not to post . . . oh, fuck it.”

The truth is I’m not qualified to review films. I have no real training in filmmaking and little interest in cinematography (or photography, by the way). I read one book on filmmaking, found the details incredibly boring and didn’t bother to finish it. The closest thing I have to anything resembling a qualification to review films is, “My parents took me to the San Francisco International Film Festival every year and once I heard Pedro Almodóvar introduce his new film, Kika.”

There are always people in our lives who tell us, “Oh, you simply must see this!” I do my best to avoid those people because when I’ve followed their suggestions I’ve wound up pissing away a perfectly good evening watching crap. Even when they manage to make their pitch, I’m a pretty tough sell. I don’t like action films. I don’t like superhero films. I don’t like horror films unless the crew from MST3K is making fun of them. Animated films turn me off completely. I dislike epic fantasies, westerns and any movie with gratuitous violence. Despite the overwhelming vitality of my libido, I’ve never seen a porn flick that got my rocks off and I generally despise sex scenes because you can’t capture the complex eroticism of the sexual experience without taste, touch and smell.

It gets better. I’ve never liked a single film made by Scorcese, The Coen Brothers, Quentin Tarantino, George Lucas, Stephen Spielberg, Bergman, Francis Ford-Coppola or his fucking daughter (though I confess to falling asleep halfway through Lost in Translation). After reviewing the list of Best Picture Oscar winners for the last fifty years, I found a total of . . . three movies I liked: The Sting, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and The King’s Speech. Looking at the AFI’s 100th Anniversary Edition of the allegedly best (American) films of all time, I found I disliked eight of their Top 10 films:

- Citizen Kane: Watching that film is like listening to U2: an egomaniacal assault on the senses.

- The Godfather: Way, way too violent and I don’t give a shit about the Mafia. Didn’t like The Sopranos either.

- Raging Bull: A bloody mess of toxic masculinity with no moral to the story.

- Singin’ in the Rain: Oh, I forgot to mention that I hate musicals, too.

- Gone with the Wind: Frankly, I don’t give a damn about this silly racist film with its dreadful acting and piss-poor casting. Vivien Leigh defines the phrase “drama queen.” Olivia DeHaviland is miscast and intensely annoying (loved her in The Heiress). Leslie Howard as a Southern hunk? Puh-leeze. Gable plays Gable like Fonda played Fonda like Cooper played Cooper like Stewart played Stewart.

- Lawrence of Arabia: I think I dozed off at least three times due to directorial excess. Lean was better with Dickens, though the quartet of Holden, Guinness, Hayakawa and Hawkins more than compensated for his obsession with scenery-heavy long shots in The Bridge on the River Kwai.

- Schindler’s List: Could hardly understand a word that dribbled out of Liam Neeson’s mouth. Typically mawkish Spielberg ending.

- Vertigo: A pretty long and torturous journey just to cure a guy of acrophobia. One bonus point for the pre-skyscraper San Francisco shots.

The only film in the Top 10 that I genuinely love is Casablanca. The other film that made the Top 10 is The Wizard of Oz, which I remember liking as a kid, but I don’t think I could watch it now.

Here’s the thing: I like films with intelligent dialogue and good stories that focus on the human condition with a minimum of cinematographic hoo-hah—the kind of films that are rarely made these days. I have a very strong preference for live theatre, which I find a far more engaging experience. I expect a movie, television show or theatrical performance to move me, both emotionally and intellectually, and for me, that happens more often in the theatre.

I allowed myself to take a total of twenty-five filmed artifacts on my voyage to the desert island. Some made the cut because they have had a lasting impact on the way I live my life; others because they’re exceptionally well-written and well-acted; and a few that always make me laugh, no matter how many times I watch them.

Due to the pandemic, I’ve been binging on TV series like everyone else on the planet and I might eventually add Schitt’s Creek to the list once Season 6 is available in France; Queen’s Gambit is another possibility. I have to see both series again to make sure they have legs. FYI, in addition to my loathing of The Sopranos, I actively despised Breaking Bad.

Films (17)

About Schmidt: I can’t think of another film that so accurately and poignantly captures the ultimate emptiness of the American Dream. All of Schmidt’s identity was tied to his job, a condition that I vowed never to replicate in my own life after seeing this movie–I never want to be Schmidt standing next to the dumpster, my life’s work piled up for the garbage collector. Favorite scene: The Dairy Queen. Outcome: I have vowed to never set foot in a Dairy Queen as long as I live.

All About Eve: I love Bette Davis because she wasn’t afraid to leave it all on the stage or set. The scene that moves me the most is the one in the penthouse when she’s giving her interpretation of events to the secretly guilty Eve-enabler played by Celeste Holm. No one has come close to capturing the existential reality of the Western woman as completely as Bette Davis did in those few minutes—the justifiable pride in her hard-earned talents and successes; the frustration that women in our society have a limited shelf life, and once we “lose our looks” we’re yesterday’s news; the hurt inflicted by another woman who was scheming to destroy her career; and the opposing force of accepting one’s cultural reality and finding happiness in a loving relationship.

In August of this year, I turn forty. When I started this blog in 2011, I swore that whatever happened I wouldn’t continue past the age of forty. You can trace the source of that pledge to All About Eve. This belief that once a woman turns forty she has moved past her prime is much more an American thing than a French thing, but just because I renounced my American citizenship doesn’t mean I’ve lost all the cultural baggage of thirty-three or so years in America. It will be interesting to see how it all plays out.

Babettes Gæstebud (Babette’s Feast): If you’ve ever wondered why I spend so much time and effort writing about music without earning a penny and never once considered monetizing my site with annoying ads, then you’ve probably never seen this movie. A woman who spends her lottery fortune on creating a one-of-a-kind artistic and sensual experience for others will always be a hero in my book. I translate that famous line “An artist is never poor” as “If you’re doing something just to make money, you’re not doing anything the world can’t live without.”

Boca a Boca (Mouth to Mouth): It’s too bad that Javier Bardem has received more attention for his heavier roles, as he is also an outstanding comedic actor who won the Goya (Spanish Oscar-equivalent) for his performance here. It’s a tight, funny movie with excellent pacing that also points out the absurdities of a society that devalues the artist and forces the talented to piss away their lives in shit jobs, humiliating themselves in the hope of getting the big break. While the film also satirizes the twisted nature of sexual obsession in modern culture, balance is restored when Aitana Sánchez-Gijón makes her entrance, reminding us of the sheer erotic power of a beautiful woman sensuously smoking a cigarette.

Il mostro (The Monster): I know he won the Oscar for his work in Life Is Beautiful but I insist that this film—hated by American critics—is Roberto Benigni’s best work. Beyond the brilliant physical comedy that always leaves me in tears, the underlying message that the authorities often get things wrong due to their inflated egos and personal agendas remains a real problem in our COVID-19-infested world.

Life of Brian: Some people have accused me of being anti-Christian, which is not true: I’m anti-all-religions. That doesn’t mean I’m on some kind of campaign to destroy religion; it just means that it’s best not to engage me on the subject. And while a film that brilliantly satirizes the gullibility of followers (whether the act of following involves religion or purist politics) is always going to appeal to me, the scene that makes this film a must-carry-to-the-island is the Biggus Dickus scene. I still don’t know how Michael Palin managed to get through that sequence without laughing.

Musíme si pomáhat (Divided We Fall): This Czech film is superbly acted, well-paced and extraordinarily moving. More than any other film I’ve seen, it reminds me of the truth that human beings are never purely good or purely evil and that the phrase “Judge that ye not be judged” should be modified to incorporate the famous words of Bobby Simone, “Everything’s a situation.” You can’t understand why a person acted the way they did unless you understand the full range of options and pressures in operation at the moment of decision.

Notes on a Scandal: Judi Dench is great as always, Cate Blanchett is pretty good, but for me the main attraction is Bill Nighy’s supporting role. I saw him on the London stage in Blue/Orange and have been a fervent admirer ever since (though his choice of films sometimes throws me off). His emotional range is breathtaking—he can switch from casual banter to uncontrollable rage in a heartbeat.

Rebel Without a Cause: This movie literally saved my life, so I will always have a tender spot for it. I think I’ve mentioned the incident in question elsewhere, so I’ll just move on.

Shadow of a Doubt: I’m not all that impressed with Hitchcock in general; even less so after reading a biography of the arrogant creep. What I love about this film is the dichotomy of good and evil as personified in Teresa Wright and Joseph Cotton—especially because the good in this case (Teresa Wright) actually tries to do something about the evil, unlike every other stupid broad in film who allows herself to be devoured by monsters or sliced up by a maniac.

Sunset Boulevard: I love William Holden and am frustrated that I can only take one of his films. This was a close call between Sunset Boulevard, Stalag 17 and Network. I figured Network wouldn’t feel too relevant on a desert island and I will always be disturbed by the fact that Peter Graves turns out to be the bad guy in Stalag 17. That’s Jim Phelps! He can’t be a bad guy and fuck Tom Cruise for trying to make him into one! Gloria Swanson is absolutely perfect here, and I will thank her until my dying days for confirming my instincts to avoid fame at all costs.

The Bad and the Beautiful: With a great cast, great plot and strong dialogue, this study of human manipulation is a brilliant film about the corrosive effects of superficial self-interests (in this case, fame and money). I’m pretty sure it’s the only Kirk Douglas film I’ve ever liked. Still, I must confess that the reason it made the cut is Lana Turner. If there’s one classic Hollywood actress I would have loved to fuck, it’s Lana Turner.

The Big Clock: I haven’t found too many people who even know about this combination film noir-screwball comedy, but I love the rapid-fire wit delivered by a superb cast that includes Ray Milland and Charles Laughton. It’s always nice when the rich and powerful get what’s coming to them. Do not attempt to view this movie if you’re drunk, high or sleepy, as you’ll miss 90% of the dialogue.

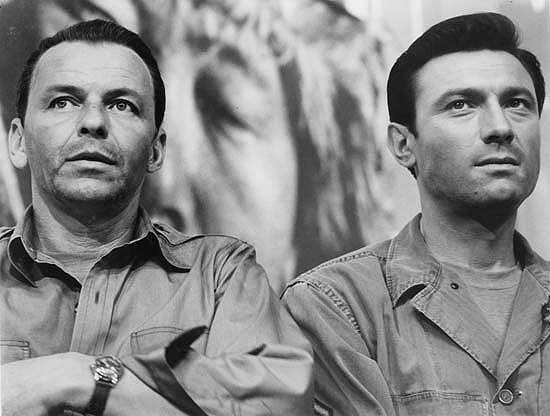

The Manchurian Candidate: This is the original, not the crappy remake. I remember watching a documentary about the film featuring Sinatra, who recalled telling JFK he was going to play the role of Captain Marco. “Who’s playing the mother?” asked the President, displaying his typically penetrating insight by identifying the linchpin character. Angela Lansbury nailed that role and Laurence Harvey pulled off the rare acting miracle of making the audience feel sympathy for his completely obnoxious character. I love the scene when Chunjin opens the door to a surprised Marco and John Frankenheimer shifts to lightning-speed close-ups of each man before they start beating the shit out of each other. I also loved Janet Leigh’s supporting role because she found the man of her dreams while he was having a panic attack, committed all her energies to his well-being and never doubted her decision for a second. I love portrayals of women who know what the fuck they want and go for it.

The Treasure of the Sierra Madre: This was a coin flip with The African Queen, but Bogie’s insanely evil laughter with his face wickedly lit by a campfire wins by a millimeter over his reaction to having his body covered in leeches.

Tristana: I had to have at least one Deneuve pick in the mix, and I chose this rather dark and somewhat uneven Buñuel film because of that one scene on the balcony that displays her “cold eroticism” to perfection. I learned a lot about dominance and submission by watching Deneuve films. Like me, I think she’s better on top.

Television Series (8)

Mission Impossible, Seasons 2-3: It’s hard to believe that Jim, Rollin and Cinnamon were only together for two seasons, but those were easily the most memorable years of the franchise. In addition to the tight plots and well-executed suspense, I love the display of the cultural artifacts of the era—Jim’s monstrously large convertibles, the uninhibited smoking and gas for 29 and nine-tenths a gallon. One of my favorite scenes is when the MI team is in Jim’s penthouse going through the final run-through and Jim looks at his watch and says they’d better get to the airport because their flight takes off in fifteen minutes. Say what? Man, I’d love to live in an era when it was possible to get to LAX and board a plane in fifteen minutes. One more thing—I’d give anything to have Barney’s little toolkit.

Monty Python’s Flying Circus: This was a no-brainer—timeless comedy focused exclusively on human absurdity never gets old. Favorite sketch: John Cleese as the boxer on his daily jog who can’t understand why a parked car is blocking his path.

Mystery Science Theater 3000: I’m the odd duck who prefers the Mike Nelson years to the Joel Hodgson years, though I respect Hodgson for creating the concept. Favorite episode: Overdrawn at the Memory Bank starring Raul Julia.

NYPD Blue, Seasons 2-6: This time span incorporates the Simone-Sipowicz era, so when I get to my desert island, I’ll use the disc containing the four John Kelly shows that open season two as a Frisbee and (since I’ll have a lot of time on my hands) figure out a way to wipe out all of Rick Schroeder’s scenes in season 6 so I can retain the Malcolm Cullinan murder trial thread.

Star Trek: Deep Space Nine: Easily my favorite Star Trek series; I’ve watched all seven seasons in order at least a dozen times. Outstanding writing and first-class acting from Avery Brooks, René Auberjonois, Armin Shimmerman, Colm Meaney, Alexander Siddig, Marc Alaimo, Andy Robinson and the many supporting cast members. Too many favorite episodes and moments to count. Fun fact: All the error messages on my computer are snippets from DS9: “THAT would have been impressive,” “This is more complicated than I thought,” and “No staring at her cleavage.”

The Americans: An endlessly fascinating, multi-dimensional drama featuring waves of unbearable tension, fabulous character development, tone-perfect period integration and intensely revealing plot and sub-plot threads. Kudos to Weisberg and Fields for superb writing and a clear long-term vision. Though Matthew Rhys has understandably garnered the lion’s share of attention for his acting, the cast is filled with superb actors in both lead and supporting roles (I’m still pissed off that Keri Russell didn’t get the Emmy for her work in Season 7). The biggest downside about binging on television series during the pandemic is you invest dozens of hours watching several seasons and the writers can’t come up with a decent ending. Not so with The Americans—the scene in the parking garage in the final episode is cinematic perfection on every level.

The Twilight Zone: The Complete Definitive Collection: Another no-brainer. Favorite episode: “Time Enough at Last” with Burgess Meredith.

The Honeymooners: The Classic 39 Episodes: What made this show so great was the unique combination of comedy and pathos, the latter consistently imprinted in the viewer’s mind through the never-changing shabbiness of the Kramdens’ apartment. Favorite episode: “A Matter of Record,” commonly known as “The Blabbermouth Episode.”

So! Now you know why I don’t review films—something to be thankful for in these challenging times. Stay safe, wear a mask and enjoy today’s annual tribute to the gladiator.

I know these recent comments I made here now might be overwhelming, but I hope that they are all at least interesting, thoughtful and constructive, specially when our tastes don’t align. I hope you liked my comments, and I wish you the best!

I talked about Yasujiro Ozu. Another deeply human japanese filmmaker is Kenji Mizoguchi. Also, few directors have been as deeply concerned, empathetic and compassionate about the historical struggles of women in society as Mizoguchi, without ever feeling excessively sentimental. I recommend checking out his film The Life Of Oharu.

I love Citizen Kane, and I loved your capsule description of your reaction to it.

Let me avoid being one of those chronic recommenders, but what’s your reaction to Preston Sturges — for example Sullivan’s Travels?

Or leaving Sturges, but not the year 1941, Ball of Fire?

Loved Sullivan’s Travels. Loved Veronica’s memoirs, too. Haven’t seen Ball of Fire yet, but I’ll put it on my wish list.

If it wasn’t for your dislike of animation, altrockchick, I’m sure you would love the japanese film “Grave Of The Fireflies”. It’s about two japanese kids living at the end of World War 2. The film portrays how cruel war is by showing the struggle of these two kids to survive in a society that has been dehumanized by the war effort. It’s unbearably sad, poignant and tragic, but also beautiful. It’s also a commentary on the culture of pride and blind faith in the Japan’s imperialism of that time. A truly powerful film that is a punch to the gut.

The film has a few scenes of dead corpses at the start, justified in the context of the characters’ development (one of the two kids sees their mother dead) and setting, but otherwise it’s pretty much non-violent. It’s all really about these two kids trying to survive in the middle of war.

Dean, have you watched Grave Of The Fireflies?

As it happens, I have seen “Grave of the Fireflies,” and it is an extraordinary anti-war film, with an impact far more profound than one could ever expect for animation. (As such, it may be the exception that, to ARC, proves the rule.) It’s definitely not like any other animated film I’ve ever seen in my life. That said, I’ll illustrate with a quote from the late, great Roger Ebert’s review of this 1988 film:

“Grave of the Fireflies” is an emotional experience so powerful that it forces a rethinking of animation. Since the earliest days, most animated films have been “cartoons” for children and families. Recent animated features such as “The Lion King,” “Princess Mononoke” and “The Iron Giant” have touched on more serious themes, and the “Toy Story” movies and classics like “Bambi” have had moments that moved some audience members to tears. But these films exist within safe confines; they inspire tears, but not grief.

Words fail me. FYI, the film is currently streaming on Hulu. I found it for free on YouTube a few years ago. — Dean

It’s a masterpiece! I agree with every word you said, expect “far more profound than one could expect from animation”. Only right from the perspective of some casuals. Yes, we are not used to see animated films dealing with these themes, animated films so grounded in reality. I laud that. But animation is also amazing because it’s a medium you can do anything with. I consider the classic Disney films, such as Snow White, Pinocchio, Bambi and Fantasia, to be amazing works of art too, but obviously with completely different purposes and virtues to Grave Of The Fireflies (and surely not the kind of stuff that ARC likes), so they can’t be compared. I also recently watched the french surrealist animated film Fantastic Planet and I love it. Animation is amazing for all forms of creative caricature, visual comedy and action in ways that live-action can’t match, such as Looney Tunes and Tom & Jerry. So, animation is a wide medium and insanely rich art form. I admire how in Japan animation doesn’t have the stigma of “kids’ stuff” that it has here in the West! It’s no surprise that a film such as Grave Of The Fireflies came from Japan, it perfectly shows the different mentality that Japan has towards animation.

Of course, we both hope that ARC can enjoy Grave Of The Fireflies at least. It really seems to perfectly suit his tastes. It’s a beautiful, poignant and sad movie that says much about our human condition.

Roger Ebert might not have been the film critic with the highest amount of technical knowledge, but I love the way he wrote about films with such passion, emotion and awe, specially when talking about his favorite films. Isn’t that what art really is all about? I also love how much he loved to talk about animation and the fantastic medium it is, like in the quote you showed. Leonard Maltin also did great work at this too. Animation is still not given the same level of prestige as live-action. But things are changing, specially among younger people. In Sight & Sound’s latest decennial poll, made last year, asking critics to say their favorite films, two animated films made into the Top 100: Spirited Away and My Neighbour Totoro, both directed by Hayao Miyazaki. The first time that any animated film gets into the Top 100. I know that ultimately such lists are pointless, and each person’s tastes and experiences with art means that there is no right or wrong Top 10, but I’m still happy about this.

Did you like all my comments here and all that I said? I admit I might have been a little too carried away by this whole discussion! LOL! Sorry.

Don’t worry, I think your comments are appropriate and enhance the discussion.

Thanks. Also, do you agree with what I explained in detail in some of my comments here about how cinema is much easier to somehow make a somewhat objective analysis than music, which I consider by far the most subjective art it exists (this is not a knock on music)? Like when I said:

“I think it’s far easier (if the person is willing to honestly and deeply discuss all the aspects of a film) to fully understand the qualities, appeal and virtues of a movie that I don’t love, but many people do, than it is with music.”

And:

“I think that good and honest discussion is always great and can make a person gain greater appreciation for a film and even someday start to truly enjoy it. But not always such discussions will make a person enjoy a specific film even though they can make a person much more understanding and respectful towards the film and why it’s so appreciated and loved.

I’m making this extra comment because my message seemed to imply that discussions always fail in make a person enjoy a film. Also, enjoyment should never be forced, I don’t want to imply such thing, despite me using the word “make”. I use “make” as either meaning something more like “convincing” someone and/or a person simply having a different experience of enjoyment of the film, an experience that is different from what the person had before, as liking what you previously didn’t. But I guess you understood what I really meant to say after all, even if I could say it better.”

Interestingly, I think you and Coppola have more in common than what you think, despite you not liking his films. I’ll make the case now.

At first, Coppola didn’t want to direct The Godfather. He had read the original book and dismissed it at first as sensationalist, vulgar stuff of gratuitous violence. He also disliked the glamourization of mafia. He accepted directing The Godfather simply because he needed the money.

Once he started writing the script and read the book again, he made sure to put his personal imput to make it far more to his liking. Coppola was always fascinated with human drama, so he wanted the film to mainly focus on the drama of the characters to a greater degree than the book. He also constantly clashed with Paramount’s executives due to creative divergences and was often on the verge of being fired. One of the conflicts was, for example, the violence in the film. The studio executives thought that Coppola had been too light on the amount of violent scenes.

Ultimately, the film was a huge critical and financial sucess. So, when Paramount asked for a sequel, they gave Coppola full creative freedom. The Godfather Part 2 continues and completely the deglamourization process already started in the first movie through Michael’s character arc. See, Michael Corleone (Al Pacino) for me is really the biggest triumph of the Godfather films, which isn’t an easy feat considering how strong the music, acting, cinematography and script are overall.

Michael is an outsider of the mafia world, he doesn’t want anything to do with the dirty business of his family. But circunstances, like the attempted murder on his father Don Corleone (Marlon Brando) force him to be involved in this. Ultimately, towards the end of the film, he is also the only son of Don Corleone qualified to manage the family’s business. In all this process, he slowly loses his humanity. Part 2 is the nail in the coffin, he loses his wife, orders the murder of his brother, he’s completely alone, lonely. The final shot of him just sitting in a chair and hair whitening is so powerful. Any trace of human warmth is gone, any glamour is now completely empty.

Michael’s story is a tragedy like the Bible saying “why should a man gain the entire world if he loses his own soul?”. Powerful. I overall don’t think that the violence in The Godfather movies is gratuitous or for entertainment. It’s surely never meant to make the viewer delighted, only horrified. Like the baptism scene at the end of Part 1, which shows how far Michael had already fallen in his ruthlessness and the size of his hipocrisy at this point.

About Apocalypse Now (which I know you didn’t mention), the film has become a big anthem for the evil of war and the supreme hell, dehumanization and hypocrisy of the Vietnam War. I don’t disagree, but it’s interesting to know Coppola’s own thoughts on this. He said that he doesn’t consider Apocalypse Now an anti-war because a true anti-war film, in his opinion, should be completely peaceful and happy. He also said “violence breeds violence. If we put more of it on the screen, people will lust for violence”. Interesting also how the film production was a true apocalypse, a hell that almost drove Coppola to the point of total insanity. Finishing the film took determination of steel.

While the first two Godfather movies and Apocalypse Now are by far the most acclaimed films in Coppola’s career, cementing his place in cinema history forever, they are not really the purest depiction of Coppola. He never really enviosioned himself directing epic, grand films. At heart, he was actually a director of minimalist character studies. The film that best defines Coppola is The Conversation (1974). He even said this is actually his favorite film of all the ones he made, the one he’s most proud of. It’s his most personal movie. And the haunting piano score is beautiful.

Pauline Kael was a very influential and popular movie critic. She was very polemic, she could be really infuriating. But what she said, in her contemporary review of A Clockwork Orange (1971), about violence in movies has always stayed with me.

“At the movies, we are gradually being conditioned to accept violence as a sensual pleasure. The directors used to say they were showing us its real face and how ugly it was in order to sensitize us to its horrors. You don’t have to be very keen to see that they are now in fact desensitizing us. They are saying that everyone is brutal, and the heroes must be as brutal as the villains or they turn into fools. There seems to be an assumption that if you’re offended by movie brutality, you are somehow playing into the hands of the people who want censorship. But this would deny those of us who don’t believe in censorship the use of the only counterbalance: the freedom of the press to say that there’s anything conceivably damaging in these films – the freedom to analyze their implications. If we don’t use this critical freedom, we are implicitly saying that no brutality is too much for us – that only squares and people who believe in censorship are concerned with brutality. Actually, those who believe in censorship are primarily concerned with sex, and they generally worry about violence only when it’s eroticized. This means that practically no one raises the issue of the possible cumulative effects of movie brutality. Yet surely, when night after night atrocities are served up to us as entertainment, it’s worth some anxiety. We become clockwork oranges if we accept all this pop culture without asking what’s in it. How can people go on talking about the dazzling brilliance of movies and not notice that the directors are sucking up to the thugs in the audience?”

Nope, not buying it. Michael Corleone wasn’t forced into anything: like all human beings, he was capable of free will and he had a choice. He chose to become a murdering monster, just like his dad, and fell in love with his power. There’s a song by the Scottish band Admiral Fallow with the line “it’s the courage to turn your back on the way you were raised.” Michael lacked that courage.

And if Coppola fought Paramount on the violence issue, he was a piss-poor fighter. I didn’t need to see a dead horse’s head, I didn’t need to see a stiletto pierce Luca Brasi’s hand, I didn’t need to see Sonny get riddled with more bullets than were used in a mass shooting, I didn’t need to see a man and woman sleeping peacefully after a night of lovemaking and wake up to machine guns piercing their bodies, I didn’t need to see Pacino put a bullet into Sterling Hayden’s head . . . The hypocrisy of the Catholic church was already well known (Popes had armies! The Vatican is loaded with gold!) and so that baptism scene was hardly insightful.

I thought Apocalypse Now was a weak interpretation of Conrad, and didn’t care at all for The Conversation. The only movie Coppola ever made that I partially liked was Peggy Sue Got Married, but he blew that one by casting Nicolas Cage (his nephew) and Jim Carrey. The only thing Coppola and I have in common is an appreciation for fine wine.

Compare and contrast Coppola “fighting” violence with the ending of The Manchurian Candidate. If Coppola had directed, we would have seen Raymond Shaw’s brain matter splattered all over the screen. Frankenheim shows him inserting the rifle barrel in his mouth then cuts to the horror on Marco’s face as we hear the gun go off. That was more than enough for me to “get it.” Coppola knew the success of the book would drive people to the theatre, so please spare me the attempt to try to purify his motives for agreeing to do the film.

Pauline Kael understood that—-but the casual use of violence in film is a hundred times more prevalent now, thanks to the violent, gun-loving culture I left behind.

To be clear, I’m not excusing Michael Corleone for falling in love with power, killing his brother and so on. Sorry if it seemed like I was justifying him. I think his arc is interesting and very convincingly done, but I get that the corruption of a person is not really something that is on my list of first things to see perhaps.

The baptism scene was more to show Michael’s hypocrisy.

Your points about the violent scenes are fair. To be clear, I don’t enjoy any of these violent scenes, far from it. I always would rather watching movies without them. But I think that in this movie case, I can accept they exist, it’s mafia after all. And the movie has too many qualities in other aspects. I respect Coppola as a serious artist even if his art has questionable aspects. But you still made interesting criticisms about the violence and I always think about Pauline Kael’s comment when it comes to violence in films as at least something worthy of keeping in mind always.

I say that Michael Corleone became worse than his father. Don Corleone was a man who still loved and cared for his family above anything. Michael ended up driving everyone away, even murdered his own brother, and becoming lonely.

I used to watch lots of movies on video, and I enjoyed most of them. Those days are long gone. Now, like you, I have an overall negative opinion of almost all films. I honestly don’t know what happened. It seems like I’m so distracted by the artifice that I can’t appreciate the art. Or maybe, just maybe, most movies really ARE as bad as I think they are.

I’m sure this is why I appreciated your reference to Mystery Science Theater 3000. “Overdrawn At The Memory Bank” is an excellent choice for a favorite episode. It has such a ridiculous plot. The fact that a well-known actor (Raul Julia) was along for the ride made it even better. I use a picture of an anteater as my icon on my Flickr page partly out of my love for that MST3K episode. Some of my other favorite episodes include “Warrior Of The Lost World,” “The Touch Of Satan,” “Space Mutiny,” “I Accuse My Parents,” “The Rebel Set,” “The Brain That Wouldn’t Die,” and “Teen-age Strangler.” There are lots of classic shorts as well. I like Joel and Mike about equally.

Congratulations! You win the Comment I Wish I’d Made Award for “It seems like I’m so distracted by the artifice that I can’t appreciate the art.” That’s exactly why contemporary movies suck.

Sorry, but it’s not a fault of the art. It’s just your personal taste. Nothing “wrong” with your taste, you enjoy the art you enjoy. But I, and I’m sure many other people too, can’t agree with your feelings about the art and what makes it unique and beautiful.

Also, I think that almost all art has the right to exist, either mainstream or ones that appeal to niche groups, such as the classic french surrealist animated film Fantastic Planet (1973).

I wonder if, based on your descriptions here of your tastes for films, you would love the work of japanese filmmaker Yasujiro Ozu. He made slice-of-life films about the lifes of typical japanese families in the 50s. His films are characterized by very slow pacing, very strong mininalism, complete avoidance of melodrama (like the typical japanese families he portrays, his films’ emotions are very subtle) and static camera. The themes of his work generally are the loss of traditions, respect for parents (he never married and always took care of his mother and lived with her until she died) and so on. God, the way I say this makes him seem like some easy moralistic director, but his work is far more nuanced than that actually.

His most acclaimed film, which is also probably one of the 10 most critically acclaimed films ever made, is Tokyo Monogatari (Tokyo Story) from 1953. It’s about an elderly couple who goes to visit their sons in Tokyo, but ultimately these sons have little time for them.

Yasujiro Ozu was always a highly acclaimed director in Japan, but his fame outside of it took a while to happen. During the 50s, Kenji Mizoguchi and Akira Kurosawa were Japan’s most acclaimed directors in the West. Yasujiro Ozu, though, was considered by distributors as being “too japanese” to be palatable for western audiences’ tastes. His work would only start to be truly known by cinephiles from outside Japan in the 70s! He had already directed his last film in the early 60s!

For more information about him and the film Tokyo Story, I highly recommend not only their Wikipedia’s articles, but also Ozu’s page in the site “They Shoot Pictures, Don’t They?”, which is also overall an amazing site cataloguing cinema’s most acclaimed movies and directors!

Thank you. I’m not familiar with his films, but the subtlety and minimalism you mentioned reminds me of the Japanese author Tanazaki, whose work I like very much. Thanks!

“Tokyo Story” is a beautiful, humble movie, ARC. And sad, in the way that life can be so sad. I can’t imagine a sensitive loving person like you would not find it deeply moving.

https://youtu.be/VFpLZwl5v80

I think this scene of the grandmother and her indifferent grandson perfectly encapsulates the pure sensibility, honesty and humbleness of the film. It would be so easy to make this scene cheaply sentimental by making the grandson say “when I grow up, I’ll become a doctor and heal you”. Instead, he is just a small kid doesn’t really care or understand this. Conflict of generations is a big theme in the film.

Loved your description of how the film is sad as only life can be sad. Ozu was perhaps the most human and sensible of all directors without being cheaply sentimental. He was honest and humble.

Great that you are interested in my suggestion!

I really feel you’re gonna love Tokyo Story and Ozu. His cinema is the total opposite of flashy or artificial. His focus is total on the characters. Like I said, he’s very minimalist and keeps the camera static. His sensibility and poignance about our average human lifes are awesome too!

It’s interesting to think that all those aspects of Ozu’s style that I talked about are probably why for so long his films were barely ever shown or known about outside of Japan. They were considered “too japanese” by distributors…

An amazing video essay on Yasujiro Ozu is “The Depth Of Simplicity” by YouTube channel The Cinema Cartography. That said, no one speaks better for Ozu’s deep humanism and care for the average life of average people than his own movies, obviously. Late Spring, Tokyo Story, An Autumn Afternoon, and so on.

I already talked about Tokyo Story before. I will say that Late Spring is about one of the themes that Ozu is more interested in his filmography: the love between parents and daughter, and their eventual separation due to society’s expectations and pressures. In the film, that Noriko doesn’t really want to leave her father to marry. And her father doesn’t want to lose her, but he feels like he has to make her marry because it’s what society expects. He loves her, and she loves him, they are perfectly happy father and daughter, but society’s expectations force them to go different paths. One can’t help but to not think about Ozu’s own life: he never married, he deeply loved his mom, he never stopped living with her, and he took care of her till the end of her life. And when she died, he would die after only a year if I’m not mistaken, and in the day of his 60th birthday. The most iconic phrase of his last film, An Autumn Afternoon, released one year before his death, is “in the end, we all die alone”.

You really have different opinions on films. For a lot of cinephiles, films are at their best when they play with cinemotagraphy, angles, editing and so on. The purely cinematic aspects of films.

Though, to be honest, I’m a casual watcher of films too. And yet, even I myself find most of your criticisms towards a lot of these films as too superficial, simplistic, questionable, baffling and even completely non-sense. I’m sorry if I’m being rude, but I really don’t want to disrespect you. I’m just being honest. And, no matter what arguments I might have (or many others who know so much more than me, and I also think it’s a lot easier to make rational and somehow objective analyses of greatness in cinema than it is with music), ultimately personal enjoyment is very subjective. No amount of theorical discussion can truly make someone enjoy a film. I think you can gain a better understanding of its qualities and why it’s loved by so many, but the pure aspect of enjoyment is another matter.

But I get that it’s not your intention to ever seriously review these films to began with, you are very honest with your limitations. I like your humbleness with the art of cinema. Honestly, even if someday I become a big cinephile, I hope to still retain humbleness towards the art and other appreciators of it.

I will only really talk about you not liking Singin’ In The Rain. Well, theb there really is no hope for you to enjoy musicals, you are right in saying you trul hate them. I think that all aspects of the film make it one of the most charismatic, uplifiting and charming works of art ever conceived by man and I’m far from a huge fan of musicals. The title song is a perfect example, perhaps the ultimate depction of joy and happiness. Escapist art at its finest. Spreading pure light and beauty to the world. And I love art like this. Like I said to you before, I don’t like the strong tendency of many people, specially supposedly “serious” art lovers, to praise more strongly stuff that is cynical, edgy, uncomfortable. As if optimistic, escapist, uplifting, happy, often populist art was somehow inferior and almost necessarily not worthy of being taken as seriously as “art”. I’m glad that Singin’ In The Rain is as acclaimed as it is despite being the total opposite of edgy and cynical.

Sad that you don’t enjoy animation, because I love it so much. It’s an amazing art. Disney’s Pinocchio is jaw-dropping for me, for example, it’s unbelievably beautiful. But, well, it can’t be helped. You enjoy what you enjoy.

Many interesting picks of films and series you enjoy also. And I may have posted here before a worse, more incomplete version of this whole. I’m not sure, but if I did, then delete the other version of this post.

Also adding another thing to comment: I think that good and honest discussion is always great and can make a person gain greater appreciation for a film and even someday start to truly enjoy it. But not always such discussions will make a person enjoy a specific film even though they can make a person much more understanding and respectful towards the film and why it’s so appreciated and loved.

I’m making this extra comment because my message seemed to imply that discussions always fail in make a person enjoy a film. Also, enjoyment should never be forced, I don’t want to imply such thing, despite me using the word “make”. I use “make” as either meaning something more like “convincing” someone and/or a person simply having a different experience of enjoyment of the film, an experience that is different from what the person had before, as liking what you previously didn’t. But I guess you understood what I really meant to say after all, even if I could say it better.

Short criticisms are what they are—superficial and simplistic—but not nonsense. What I wrote makes perfect sense to me, and my brief comments proved the premise of the essay: I’m not qualified to review films and I don’t have the passion necessary for such an effort.

You have the right to like Singin’ in the Rain, I have the right to feel that the fundamental artificiality of musicals is off-putting—and the comment was a general comment about all musicals, not a specific condemnation of that particular film. If I were to review the soundtrack without having to watch the film, I would probably be more generous. I think Barbra Streisand’s vocal on “Don’t Rain on My Parade” is fabulous, but watching Funny Girl made me cringe. My views are consistent with my views on opera—I can appreciate the music, but not I have to watch people in silly costumes sing it.

I understand that the artificiality of musicals might turn off some people. I think it’s part of the escapism. A guy once said that musicals operate by this logic: when emotions become too strong for speaking, you sing. When they become too strong to be expressed with singing, you dance. That’s the basic logic of musicals. I’m not saying that you should like this, I’m only explaining what I know about musicals.

Maybe me using the word “non-sense” to describe your many types of criticisms about many movies here was wrong, I admit. Still, they were very questionable, baffling and superficial about the point of these films, these criticisms are easy to tear apart (specially because they are mostly criticisms of political and moral nature rather than cinematic).

But, like you said before, you don’t intend to review films and is well aware of your limitations for such. So, all my points in the previous paragraph don’t matter really. I admire your humbleness. I’m still overall a casual film watcher and I hope to retain that humbleness towards the art of film even if I someday become a hardcore cinephile.

Also, do you agree with my thoughts that cinema is an art far easier to deeply analyse in a somewhat objective fashion than music? I always strongly felt that yes. I think it’s far easier (if the person is willing to honestly and deeply discuss all the aspects of a film) to fully understand the qualities, appeal and virtues of a movie that I don’t love, but many people do, than it is with music. I strongly feel that no art is as subjective as music.

I explained better my thoughts about this in all my previous comments in this page, I hope you liked my comments. Also, my criticisms towards your comments are not meant to be disrepectful, sorry if it came out that way.

Oh, one thing I had forgotten to say about why I love animation: maybe the best thing about it is that imagination is your only true limit. You can also pull of a lot of visual comedy and silly scenarios that wouldn’t work in live-action. Like Looney Tunes. And action scenes too (but you said you don’t like action, so it doesn’t matter for you).

Vertigo is a film with some divisive elements. Many love it unconditionally, other people have some criticisms of it that are in a wide spectrum in how fair and understandable are.

I will say this though, and it’s the biggest tragedy in Vertigo (even more than the way that Jimmy Stewart’s character, Scottie, is cured of acrophobia): it’s how his character ends up completely ignoring Midge.

For most of the film, Scottie is an empathetic character. But he starts to lose a lot of our empathy when his obssession grows to a point that he is willing to completely force an unknown woman, Judy, to become exactly the woman he fell in love with, Madeleine, completely disregarding her individuality. And she complies because she loves him, and because she acted the role of Madeleine before, as Scottie will eventually learn he was victim of. Their romance is completely fucked up and sad in their obssessions. The fact that Jimmy Stewart, the quintessential american nice guy, plays the role of Scottie really shows how Vertigo is a dark and unsettling distortion of the classic Hollywood romance and its tropes. Exploring the dark and twisted, distorted sides of human nature that are often hidden within us, but we are not aware of, really is one of Hitchcock’s biggest concerns in his body of work.

And now I actually talk about Midge. Throughout the whole film, she is such a likeable and nice woman, and so supportive of Scott. But he becomes so blind by his obssession with making real this idealized woman that only exists in his mind (Madeleine) that he completely forgets Midge in his life, and the actual healthy relationship he could have with her. Ultimately, Midge really is the biggest victim in the film, and its most likeable and grounded character. And sadly, the errors of Scottie in neglecting the good and healthy people of his life in favor of a toxic obssession that corrupts him into cruel manipulation is way too common in real life.

Talking now about Lawrence Of Arabia by David Lean: I understand that the way he loves to linger on shots of majestic vistas is not for everyone, though I personally love it, as it gives the film so much of its grandeur (it’s really one of those films that benefit the most from being seen in theaters). As beautiful as those vistas are, the ultimately most interesting element of the film, what makes it so fascinating, is the protagonist T.E. Lawrence, interpreted by Peter O’Toole, and I feel you would probably like the film a lot more if Lean trimmed a lot of the length in his grand shots, and devoted as much as time as possible focusing on Lawrence. Nevertheless, this is still honestly one of the most fascinating character studies in cinema for me. It’s really overwhelming for me to talk all about this, hence why I would rather not attempt this daunting task now, and instead recommend a good video essay on YouTube called Lawrence Of Arabia Tragedy Of The Conqueror. I think it says almost everything I could ever say.

On your comments regarding your love for Casablanca: I will add that Humphrey Bogart’s performance as Rick is a a truly amazing example of how fantastically subtle he was an actor. His performance generally doesn’t have many big outbursts of emotion, the kind that calls the attention of everyone to how amazing you are as an actor. Instead, Bogart conveys so much with his eyes and small twitches in the muscles of his face, like all of his reactions and facial expressions when seeing Ilsa and first talking with her for the first time after years, or his look right before the flashback telling him and Ilsa’s past.

I love this quote from Bogart about himself as an actor:

“I’m not good-looking. I used to be, but not anymore. Not like Robert Taylor. What I gave got is I have character in my face. It’s taken an awful lot of late nights and drinking to put it there. When I go to work in a picture, I say ‘don’t take the lines out of my face, leave them there'”.

Damn, I’m sorry. I replied to my own comment instead of your post, I meant to reply to your post!

“My Dinner with André”? All they do is talk, and in the end the most important thing is THAT they talked, and not what André said.

I loved that movie!