Donovan – Fairytale – Classic Music Review

The Set-Up

One outcome of my trip to Nice last month was that I agreed to review two albums by Donovan.

Okay, I was drunk.

We were having dinner at Di Yar, my favorite restaurant in Nice. It was a very pleasant night, not too warm, not too cold, with jazz, the chatter of passers-by and good conversation in the air. As if by magic, my wine glass continually filled with a deep red liquid which in turn continually found its way to my mouth. Two and a half hours into the experience, my father brought up Donovan.

“You can’t ignore him.”

“Wanna bet?”

“He was a major force in the mid-sixties. He had hit after hit. He was one of the spokespeople of the generation.”

“It sounds like you’re talking about a bicycle repairman.” I giggled at my wit. We all giggled for about five minutes, trapped in a moment of contagious laughter.

“Give him a chance. You gave Dylan a chance and you liked him.”

“One album!”

“Come on. Do it for your dear old dad.”

“Which one?”

“Start with Fairytale and then . . . ”

“And then? And then? I said which one!”

“But his career had two distinct phases. You can’t do Donovan without doing the folk period and the psychedelia.”

“But I don’t want to do Donovan at all! I’ve had Coltrane on my list for months!”

“Coltrane can wait. Coltrane’s eternal. You’ve been on a sixties jag lately and Donovan is the biggest gap in your library.”

I had to give the bastard credit for knowing my weak spot and exploiting it. I hate having gaps in my library; it was the primary reason I decided to keep the blog going.

I took a big long drink from my bottomless wine glass. “Okay, I’ll do Donovan—but I’ll do it in my own way and don’t expect any favors. And I will get payback for this.”

“Hey. I’ve lived with your mother for decades. I understand payback,” my father replied. My mother smiled wickedly and contentedly and raised her glass to me in a victory toast.

Donovan vs. Dylan

Although I think men who take advantage of a lady when she’s inebriated are the lowest of the low, once I make a promise, I stick to it. I spent the next morning immersing myself in Donovan music and lore despite a horrible hangover alleviated slightly by oral sex and listened to the two records—Fairytale and Sunshine Superman—almost continuously over the next couple of days.

By Wednesday, I reeked of patchouli oil.

Fairytale was Donovan’s last album of his very brief folk period, which consisted of a total of two albums. The first was “the one with ‘Catch the Wind’.” I listened to it once and decided that the only reason he landed a recording contract was because he was a scruffy guy with a guitar and the record companies were buying up all the scruffy guys with guitars to cash in on the folk craze. They’d do the same thing with the San Francisco Sound a couple of years later and destroy Moby Grape in the process.

The Brits were latecomers to the folk craze; The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan came out in the U. S. in 1962 but didn’t become a number one in the U.K. until 1964. Slow boats, I guess. Donovan was greeted and hailed as the British response to Dylan, so let me address that issue upfront.

First, I have no idea why the British felt they needed to ape American folk music when their own folk tradition is so much richer (they’d finally figure that out a few years later). Second, it’s hard to fathom that they would feel the need to musically compete with the Americans at a moment in history when they were giving the world Lennon, McCartney and Ray Davies.

On the Dylan-Donovan issue, there is no comparison. Dylan and Donovan shouldn’t be mentioned in the same breath. You can take any verse that Bob Dylan ever wrote and compare it to anything Donovan ever wrote and Dylan would win every time. Dylan had superior intellect, social insight and a decided flair for language. Donovan wrote some nice songs and one or two better-than-nice songs; Bob Dylan wrote several timeless masterpieces. Even this dumb blonde can see that Dylan is far superior, and I’m not even a Bob Dylan fan!

So, let us consider Donovan on his own merits and leave the comparisons behind. I think Fairytale is a nice piece of work where he shows flashes of original talent that I wish he would have exploited further instead of repackaging himself as The Hippie Guru. We’ll get into that aspect of his career when we look at Sunshine Superman; meanwhile, we will consider the value of Fairytale. I’m reviewing the U.K. version to avoid having to listen to “Universal Soldier,” a Buffy Sainte-Marie song I loathe in the extreme despite my commitment to pacifism and the firm belief that all violence should be voluntary, consensual and limited to the bedroom.

Finally, the Review

“Colours” opens the album, a pleasant little folk song with guitar and scratchy banjo. The lyrics are ho-hum but inoffensive . . . until he gets to the last verse and tries to season the song with significance.

Freedom is a word I rarely use

Without thinkin’, mm hmm,

Without thinkin’, mm hmm,

Of the time, of the time

When I’ve been loved.

As anyone who watched the movie Woodstock knows, freedom was a big meaningful word in the sixties. The Freedom Riders started the ball rolling, and the concept was later applied to many different acts of liberation: free love, free Huey, free-dom! Read that verse again and tell me, what the fuck does he mean? I don’t think he knew: I think he threw in the word “freedom” because it was a marketable word at the time. I understand the possible connection between “being free” and being in a relationship, but that’s small-f freedom—and if that’s what he’s talking about, the song becomes even more trivial and the use of the word “freedom” is gratuitous at best. “Colours” highlights a tendency Donovan displays too often on this album: he’ll write a “wrap-up verse” where he intends to capture the essential meaning of the song in a few lines; sort of like, “and the moral of the story is . . . ” It doesn’t work because in the wrap-up verses attempts to imbue meaning where there is none to imbue.

We see this in the generally more interesting “To Try for the Sun,” a song based on his real-world travels with his pal Gypsy Dave. There is, of course, the gratuitous use of harmonica (it’s hard to write about many Donovan songs without using the word “gratuitous”), but he does manage to pull together a decent verse now and again:

We huddled in a derelict building

And when he thought I was asleep

He laid his poor coat round my shoulder

And shivered there beside me in a heap.

The “wrap-up” verse “Mirror, mirror hanging in the sky/Oh, won’t you look down what’s happening here below/I stand here singing to the flowers/So very few people really know” is both gratuitous and nonsensical. It also diminishes the imagery of the earlier verses by turning experience into abstraction.

After two pretty basic folk songs, “Sunny Goodge Street” comes out of nowhere with its opening cello and soft jazz feel. His subdued, limited voice is more suited to this style, as he would demonstrate again in songs like “Mellow Yellow.” The lyrics are quite vivid, capturing the urban London fringe scene that eschewed those raucous lads playing at the Crawdaddy Club for the coolness of Charles Mingus:

On the firefly platform on sunny Goodge Street

Violent hash-smokers shook a chocolate machine

Involved in an eating scene.Smashing into neon streets in their stonedness

Smearing their eyes on the crazy cult goddess

Listenin’ to sounds of Mingus mellow fantastic.

“My, my”, they sigh,

“My, my”, they sigh.

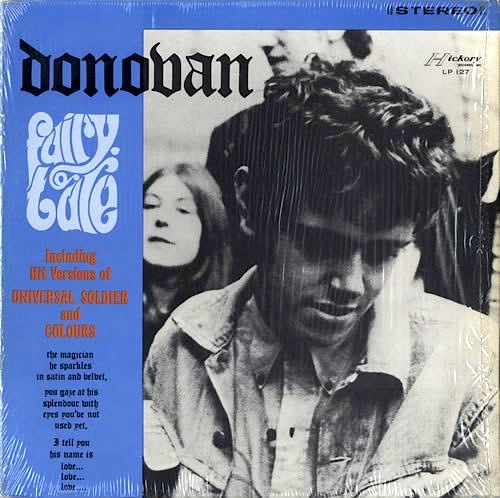

Judy Collins ruined this song on her otherwise brilliant In My Life album with an over-the-top circus arrangement; Donovan captures the hashish-tinged mood perfectly with a jazz combo sound. The late Harold McNair contributes a superb flute solo that adds to the coolness of the scene. Unusual for a Donovan song is the chord complexity; he’s usually a two or three-chord kind of guy. There is, unfortunately, a ridiculous wrap-up verse featured on the cover that has no connection whatsoever to the experience described in the other verses. Since the album came out only a few weeks after the word “hippie” was first used in print to describe a new wave of beatniks in San Francisco, we can’t indict Donovan for attempting to capitalize on a craze just yet (we’ll take care of that in the Sunshine Superman review):

The magician, he sparkles in satin and velvet,

You gaze at his splendor with eyes you’ve not used yet

I tell you his name is Love, Love, Love.

Whether the verse is a sincere but disconnected celebration of the power of love or an advertising jingle, I have to say that “Sunny Goodge Street” is probably my favorite song in his entire catalog.

(There’s an alternative video on YouTube where Donovan plays the song acoustically while ludicrously dressed in Renaissance costume if you want to go there. I decided to spare him the embarrassment by not posting it here.)

Bert Jansch’s “Oh Deed I Do” comes next, one of Bert’s lesser numbers and a disappointing follow-up to “Sunny Goodge Street,” as Donovan’s voice and guitar both sound out of tune. The dissonance was deliberate in “Circus of Sour,” a playful number with witty lyrics . . . that Donovan didn’t write (a mystery man by the name of Paul Bernath was responsible). Oh, well. Donovan’s performance is relaxed and cheery, a tone that works for him much better than his occasional tendency to take himself too seriously.

He did pen the next track, “Summer Day Reflection Song,” a quiet little ditty capturing random thoughts while watching a cat. It’s nice background music for a quiet Sunday but not much more. He adapted “Candyman” from the British traditional version, adding a reference to Morocco to confirm the Candyman’s status as a “drug dealer.” I wasn’t impressed. “Jersey Thursday” demonstrates his lifelong obsession with colors as adjectives, the hallmark of many a lazy poet. He would finally make it through the whole Crayola box by the time he got to the second verse of “Wear Your Love Like Heaven,” where after using up Prussian blue, scarlet and crimson, he came up with Havana lake, rose carmethene and Alizarian crimson for no apparent reason whatsoever.

Did I mention that I think Fairytale is his best album?

Next comes a song that drives me to distraction, “Belated Forgiveness Plea” (also known as “Isle of Sadness”). I can forgive Donovan for inventing a fake place called Trist la Cal that sounds terribly and trendily exotic, but I can’t forgive him for his careless use of symbolism. As much as he was in love with colors, Donovan was heads over heels about seagulls. The refrain to this song is “But the seagulls they have gone/The seagulls they have gone,” as if their departure represents the ultimate existential isolation experience. He actually sings, “There is nothing left for me now/The seagulls they have gone.” Wow. That’s a serious attachment.

Look. I grew up in San Francisco. I know seagulls. Seagulls are nasty, squawking birds who go out of their way to crap on people. They symbolize shit! I can take you to a coffeehouse in Victoria B. C. where the north wall is covered in seagull feces from their regular bombing runs on coffee lovers who dare to take their java breaks at an outside table. In various locales, seagulls have defecated on my shoes, my coat and even my hat—and thank God I was wearing a hat because seagull dung has a half-life of 500 years! You can never get rid of that smell! Fuck seagulls! What a . . . crappy use of symbolism!

Ah, but Donovan lived in a fairytale world where seagulls never poop.

“Ballad of a Crystal Man” is a protest song, but this one lacks the cachet of “Eve of Destruction” or “The Times They Are a-Changin'” because it’s not very well-written. Beginning with an intensely annoying single note on the mouth harp over a rapidly picked guitar (he even repeats that awful note for several excruciating measures in the instrumental passage), the song is tedious in the extreme and contains some of the worst syntax I’ve ever read:

On the quilted battlefields of soldiers dazzling, made of toy tin

The big bomb like a child’s hand could sweep them dead just so to win

Whazzat? Huh? He proceeds to compound the problem with truly weird juxtapositions:

As you fill your glasses with the wine of murdered Negroes

Thinking not of beauty that spreads like morning sun glow

Whafuck? Hello? You mean if they had filled their minds with images of beauty those murderous racists wouldn’t have engaged in lynching? Do you really mean that?

I pray your dreams of vivid screams of children dying slowly

And as you polish up your guns, your real self, be reflecting

Whew! I can’t even begin to diagram those sentences! I’ve accused Dylan of excessive obscurity at times but at least he wrote coherently enough so that I could tell it was obscure. This song just seems like random fragments from other protest songs jumbled together to attempt to demonstrate that Donovan was hip enough to have a social consciousness. What it demonstrates is that he was, for the most part, a lousy poet.

So was Shawn Phillips, who wrote the childishly gruesome “Little Tin Soldier” that follows. The storyline and conclusion are so ridiculous that you simply had to be stoned to appreciate them. Stunningly and completely out of the blue, Fairytale ends on a strong note with “The Ballad of Geraldine.” This is a first-person narrative told from the perspective of a young woman who finds herself knocked up and abandoned by her footloose lover. As she wanders the streets and considers her fate in a time when unmarried pregnancy was taboo, she makes some startling admissions and has a cold revelation:

My baby is a-growin’ as a-growin’ it must

If I were to lose it, it would grieve me

My love is so helpless and I’m wonderin’ what to do

Oh, how I yearn to help him

Oh, we could go to the land of your choice

Where the false shame won’t come knockin’ at our door

I’ve a feelin’ in my heart and it’s crushin’ all my hopes

I think, I’m gonna be hurt some more

It’s difficult for me to believe that anyone could be so self-sacrificing as to call her scumbag lover “helpless” and want to comfort him, but I suppose a person with extremely low self-esteem might confuse love and sacrifice. Had Donovan ended the song on that verse, I’d dismiss him as a sexist idiot, but by including Geraldine’s realization “I think I’m gonna be hurt some more,” he shows that he’s intelligent and sensitive enough to understand that life doesn’t always end like a fairy tale.

Okay, that’s Fairytale. I see some good stuff, some potential and a few glaring deficiencies that need correction. While I may have come across as scathing at times, I don’t think it’s a bad album. To prove to you that beneath my hard leather-clad exterior I’m really a very nice person, I’m going to let you in on a little secret . . . I’ve cracked the mystery of time travel. After listening to Fairytale, I decided I wanted to help the poor lad, so I jumped into my time portal, zoomed back to late 1965, easily located Donovan hanging around Carnaby Street and invited him out for a bite to eat.

“Kid,” I said, lighting my cigar at the end of the meal, “The way I see it, you’ve got three possible directions. You could forge a career out of soft jazz with urban scene lyrics—you’ve got some potential there. You could write songs told in the first-person about people in tough situations . . . maybe sell them to others with acting skills who can sing a little bit better. Or, you could write songs for children. But the pure folk angle ain’t gonna fly— fuggedaboudit! You’ll never be Dylan in a million years and you’ll just be seen as the annoying little kid who’s tagging along with the big guys. And please, please, please, forget about the psychedelic scene—it’s a passing fad and you’ll live to regret it. Whaddya say, kid?”

He told me to bugger off! And left me with the tab! How rude!

And as I leaped back into the time portal, I could hear the unmistakable sound of a seagull splat behind me.